When Global Rules Weakened: Somaliland and India’s Perspective

This article examines a profound shift in the international system once described as the “rules-based international order.” That framework has visibly weakened in recent years. Israel’s recognition of Somaliland last week stands as a stark symbol of that erosion, coming at a moment when global politics is increasingly shaped by power and interests rather than shared norms and principles.

Israel’s decision coincides with a wider set of global pressures: Ukraine facing demands to trade territory for peace, China threatening to use force to absorb Taiwan, and the United States quietly downgrading the centrality of international norms in its 2025 strategic outlook. By 2026, it has become evident that the post–Cold War normative framework has lost much of its capacity to restrain the ambitions of major powers.

For India—and the wider South Asian region—these developments carry two sobering lessons. First, global norms alone do not guarantee a state’s territorial integrity. Second, sovereignty is not a privilege bestowed by the international community, but a political asset that must be continuously protected through internal cohesion and external vigilance.

Although Israel’s move has drawn widespread condemnation, few expect a reversal. Tel Aviv’s decision reflects a hard-nosed strategic calculus. Somaliland occupies a highly consequential geopolitical location at the mouth of the Red Sea, linking the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean. From Israel’s perspective, engagement with Somaliland offers maritime access, strategic depth, and an expanded regional footprint.

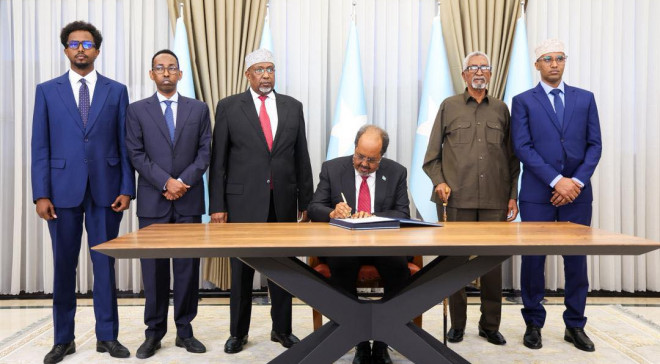

This calculation has punctured a long-held assumption of the post–Cold War order: that violations of sovereignty would trigger unified international resistance. Had that assumption held, Somalia’s territorial integrity would have enjoyed universal support. Instead, the global response has been fragmented. Several Arab states have issued strong denunciations, while others with economic and strategic interests in Somaliland have chosen ambiguity or silence. Some African governments have spoken out, while others have remained cautious. Ethiopia, a landlocked country seeking maritime access through Somaliland, has remained silent. Ethiopian leaders have previously remarked that “Addis Ababa will not be the first to recognise Somaliland, but it will not be the third either.”

For more than three decades, Somaliland has functioned as a de facto state without formal recognition. This uneasy balance reflected a compromise between political reality and legal principle. Israel’s recognition has disrupted that equilibrium and highlighted a broader truth long evident in international practice: when material interests collide with political norms, the latter are readily sacrificed.

The idea of a “rules-based international order” gained prominence over the past decades, yet experience has shown that rules without enforcement amount to little more than rhetoric. Across Asia, Europe, and beyond, the pattern is consistent—when power asserts itself, norms retreat.

India itself is not immune to these contradictions. While New Delhi strongly defends territorial sovereignty in Asia, it remains cautious in confronting actions taken by partners with whom it maintains close relations. On Somaliland, India is likely to pursue diplomatic balance rather than moral posturing, mindful of its strategic stakes in the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa, and its broader relationships with African and Middle Eastern partners.

The Somaliland episode ultimately exposes a deeper crisis of sovereignty in the twenty-first century. Borders today are challenged not only by military force, but through economic pressure, strategic investments, and digital influence. In this environment, smaller states cannot rely on international declarations alone. They must strengthen internal unity, maintain credible deterrence, and exercise regional leadership.

The article concludes that India faces three clear priorities: reinforcing domestic political cohesion, sustaining credible deterrence, and exercising effective regional leadership. Without these, external powers will continue to exploit regional fractures to advance their own interests—as they have done repeatedly in the past.

Author: C. Raja Mohan Originally published in: The Indian Express